A University Student’s Search for Lasting Happiness

By Aadam Sherazi • 3 min read

By Aadam Sherazi • 3 min read

WHEN YOU’RE YOUNG, it’s easy to believe happiness is something you find—somewhere, in someone, or after some big achievement. After experiencing some difficulties in high school—loneliness, irritability, lack of motivation—I was convinced I needed a fresh start. With the right conditions, I assumed life would get better. University, I thought, was the answer to everything I felt was missing.

After much back-and-forth, I finally convinced my parents to let me attend a university a couple of hours drive away from home. Move-in day felt like the start of something special—as my parents helped me settle into student residence, a sense of freedom and possibility was in the air. I was sure the change of scene would transform everything. But once I got to campus, reality was more complicated. There were endless ideas about how to live: partying, studying hard to secure a well-paying job, climbing the social ladder. Even with new friends and newfound independence, I couldn’t shake the familiar undercurrent of discontent.

Looking back, I now understand why. I had always assumed happiness required something outside of me—relationships, new experiences, career success. It never occurred to me that it could be something I already had. I never considered that qualities innate to all of us could be the genuine source of happiness. To me, contentment was always a destination—somewhere I’d arrive once everything finally fell into place.

During this time, I became deeply interested in spirituality and religion. I had grown up in a Muslim family, attending Islamic school and participating actively in religious activities. It was a huge part of my life, but strangely, I never really felt connected to it at heart. I prayed to God in moments of need, but there was always a disconnect—I knew how important religion was supposed to be, but I wasn’t actually conscious of it as part of who I was.

At the same time, my studies exposed me to scientific explanations of the mind and behavior. Psychology and neuroscience classes started unraveling the mechanics of human emotion and cognition. Science explained how the brain worked, but it didn’t satisfy my longing for purpose and meaning.

This led me to explore other religions and spiritual beliefs, searching for truth, clarity, and deeper meaning. One day I stumbled across an interview with Daniel Goleman discussing brain studies on “Olympic-level meditators.” I didn’t know it then, but one of the first people studied was Mingyur Rinpoche. The idea that meditation could transform the brain fascinated me. If mental training could reshape the brain, then it made sense that it could reshape one’s experience of life. For the first time, I considered that happiness might be more about the mind than the world outside.

“I had expected transformation, but all I found was the noise of my own mind, louder than ever.”

— Aadam Sherazi

Driven by this curiosity, I dove headfirst into meditation. At first, I saw it as a way to create some “special state of mind”—a blissful escape. I sat each day with sky-high expectations, waiting eagerly for something magical. Instead, I found an endless train of mundane thoughts—distractions that carried me away before I even noticed. Twenty minutes would pass, and I’d realize I had spent most of it lost in daydreams and memories.

It was disheartening. I had expected transformation, but all I found was the noise of my own mind, louder than ever. Searching YouTube for guidance once again, I was fortunate to discover Mingyur Rinpoche’s Joy of Living teachings, and everything began to change. His explanation of meditation wasn’t about chasing extraordinary states of mind; it was about working with the ordinary ones. He taught that lasting happiness doesn’t come from transforming outer circumstances but from transforming ourselves—from learning to be present and open-hearted.

What followed was a journey of ups and downs. Progress certainly wasn’t immediate, but after years of practice significant changes had begun to accumulate. I became less reactive and rigid, more open, patient, caring, and understanding. Even in my studies and creative projects I began finding success in challenges greater than ever before. With clearer self-understanding, everything flowed more smoothly. I was no longer fighting with feelings of boredom or searching for an escape. Most importantly, I started recognizing and appreciating what was there all along. Contentment wasn’t something I had to chase down and grasp onto.

Like many people starting their adult lives, I used to think happiness required a perfect relationship, a prestigious job, a life-changing experience. Mingyur Rinpoche’s Joy of Living teachings showed me that true happiness doesn’t depend on where you are or what you achieve—it’s about the condition of our own minds. Now I understand that happiness is about how I relate to my experience, whether it’s pleasant or difficult. That understanding has shaped not just my university years, but the way I see the rest of my life unfolding.

May 2025

Aadam Sherazi is a 23-year-old with a deep interest in philosophy, science, and technology. An aspiring dentist, Aadam appreciates the hands-on practice and the opportunity to connect with people from all walks of life. When he’s not in a meditation sit, you can find him grooving to the melodies of his favourite bands.

Learn meditation under the skillful guidance of world-renowned teacher Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche at your own pace.

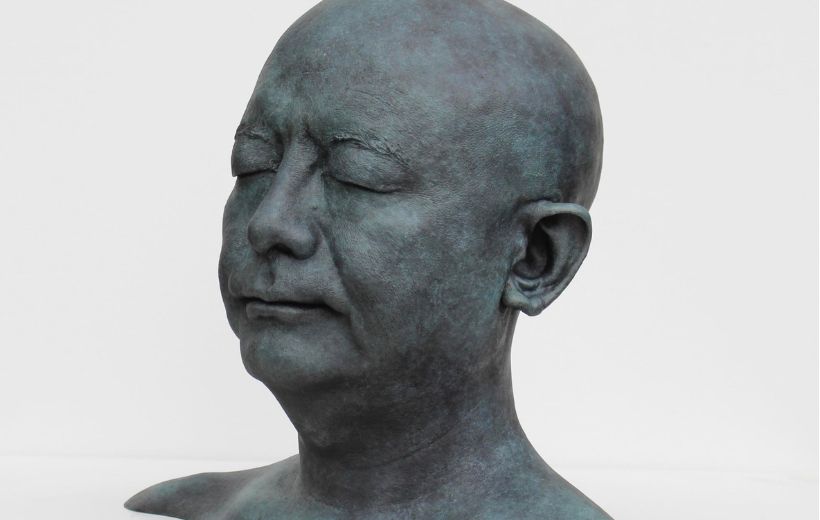

A German artist shares the bronze he made of Mingyur Rinpoche, part of a larger collection of Buddhist masters in our day and age.

Deadlines, competition, pressure — the concept of “burnout” to describe a sense of nervous exhaustion has been around since the 70’s, but never has the feeling of burnout been as prevalent as it is these days. In a situation that’s demanding too much of us, it’s natural to experience burnout. Still, there are certainly a…

“The invitation from Rinpoche, which can be found in the Joy of Living teachings, is this: can we learn to stay with the pull of craving in a way that’s balanced, open, and spacious.” – Stephanie Wagner

If you enjoyed reading our articles, please join our mailing list and we’ll send you our news and latest pieces.